The Fox Point Hurricane Barrier and the Providence “Renaissance”

A presentation for the symposium Providence Modern (1945-1995): Architecture, Design, Planning, Culture; Providence Preservation Society, October 9, 2025.

Providence, Rhode Island is on the northwestern coast of Narragansett Bay, which is part of the ancestral homelands of the Narragansett people.[i]

In 1973, news reporter Carol McCabe wrote an article for the back pages of the Providence Sunday Journal about a witches’ coven. Members of the group included a “nervous businessman” and an “affable truck driver,” among others who preferred to remain anonymous. Coven leader Ronnie Davey, on the other hand, was eager to talk. She shared a recurring vision with McCabe in which downtown Providence, a former tidal marsh and riverbed, succumbed to a terrible flood:

“In my vision, it has been raining all day. I am standing in the Outlet [department store] parking garage and I see a huge wave coming towards the Fox Point Hurricane Barrier. As it approaches, the wave is as high as the Industrial National Bank Building. The wave crests at the dam, then rolls into the city. I find myself standing in water to my hips.”[ii]

For Davey, the scene portended a near-future deluge. And yet, in her quoted words to the reporter, Davey seemed less-than-certain of its place in time. She tried to pin a date, but the very contents of the vision made it hard to say for sure:

“It is cold, which means it is a winter month, and it is just getting dark, which means it must be about five or six o’clock. The stores are open so it might be a Thursday night, I think. People are wearing clothes that look like the 1920s—long skirts and big fur jackets. All of these things make me think it might be this year, and another reason is that other people have begun picking it up in their dreams.”

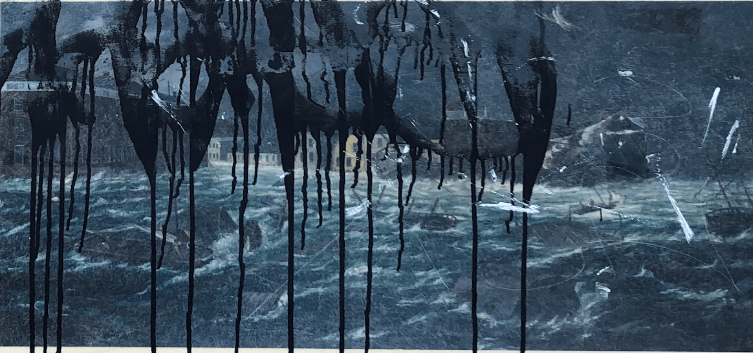

To older residents of Providence, Davey’s vision might have sounded more like testimonial than prophecy. Downtown had flooded under tidal waves before. Hurricane Carol of 1954 delivered over 13 feet of water to the partly filled land of the Financial District, where the Great Salt River used to be. The Hurricane of 1938 was similarly monstrous (and it’s worth noting here that the word monstrous is a derivative of the Latin monere, which can mean “to remind, bring to (one’s) recollection.”)[iii]

The one thing that most sets Davey’s vision apart from these historic deluges is “the dam” where she sees the wave crest before rolling forward. Officially named the Fox Point Hurricane Barrier (FPHB), the dam had been built in 1966 by the Army Corps of Engineers in the wake of Hurricane Carol expressly to preclude storm surges from ever wreaking havoc on the district again.

There are plaques affixed to certain buildings in downtown Providence showing high water marks of past storms. 12 feet, 13 feet, even 15 feet; it can be a little unnerving, when standing beneath those lines, to think about the full magnitude of what they mark. Waves dragging cars and utility poles, ships hurled against the sides of buildings, water rushing into ground floors as nine-to-fivers huddle fretfully above. People everywhere scrambling for high ground, with no idea of when or how the inrush will end.

As the plaques attest Providence has been flooded many times before. The 110 mph winds of Hurricane Carol delivered at least twelve feet of water to the streets of downtown. Kennedy Plaza, the regional transit hub and public square that occupies land where the Great Salt Cove used to be, was completely inundated (you could have rowed a boat from the Biltmore Hotel to the foot of College Hill). 19 people died in that storm.[iv]

Carol was not the first, but the second “hundred-year storm” to hit the city in only sixteen years.[v] Still fresh in many people’s minds, the Hurricane of 1938 was similarly monstrous, flooding the downtown district with as much as 15.8 feet of water. Along South Water Street, waves and winds leveled rows of old warehouses and shipping-related structures, bringing a maritime district in decline to a decisive end. The Hurricane of 1938 carried 95 mph winds and killed 232 people across Rhode Island.[vi] A century earlier, the Gale of 1815 delivered almost 12 feet of water to the inner port where downtown had just begun to rise. Weybosset and three other bridges were carried away. Nearly every ship in the harbor was rent from its moorings, and the buildings standing on the wharves were swept away.[vii]

After Carol, it was clear that the scattershot recurrence of these storms had become a huge liability for downtown businesses, from department stores to manufacturers, who were already seeing their profits decline by the mid-1950s in the face of competition from new suburban outfits.[viii] Property loss from Hurricane Carol reportedly cost $50,000,000, or roughly half a billion in 2023 dollars.[ix] Subsequently, any threat of a storm surge prompted a flurry of emergency preparations—laying sandbags, boarding up windows, and moving equipment and merchandise to higher ground—that exacted high costs in terms of revenue and labor.[x] For downtown interests, it was another reason to be worried about the district’s future economic viability. One business owner remarked the following year that “hardly a day goes by that we don’t judge some further (company) outlay by asking ourselves whether we will get flood protection or move.”[xi] The governor at the time spoke on behalf of this cadre when he remarked that “people cannot be expected to make large capital investments in an area where their investments are threatened by recurring disaster.”[xii] For patrons, the flooding only added to a shared sense that whatever luster the old city center used to have was fading.[xiii]

It was in the two or three years after Carol that officials, under pressure from groups like the merchant-led City Hurricane Committee, began “to consider coastal flood protection in earnest.” [xiv] The USACE stepped forward in 1956, with the support of Rhode Island’s congressional delegation and the Providence Chamber of Commerce, with two complimentary plans for flood protection. One plan called for a barrier at Fox Point, on the far edge of downtown. The other called for “a series of rock barriers in lower Narragansett Bay.”[xv]

The plan for the lower Bay did not survive an upswell of “near unanimous opposition” on the part of the statewide public, who feared that a giant dam would adversely impact navigation, water quality, salinity, recreation, and marine life. The USACE dismissed these concerns and held to its core plan until the mid-1960s, but members of Rhode Island’s congressional delegation were not willing to put their names on the project for fear of electoral retaliation, and so it never secured the needed federal funding.[xvi]

The Fox Point Hurricane Barrier was far less controversial. The only organized opposition to that proposal, according to contemporary news reports, was led by the Allens Avenue Businessmen’s Association, which represented industries along the river outside of the protected area in the Port of Providence district.[xvii] Then as now, the outer harbor port was a hub of fossil fuel handling and other heavy industries, all in the Bay’s coastal floodplain and therefore vulnerable to surge-related disasters, but the proposed FPHB would do nothing to protect them, and the barriers planned for the lower Bay were perceived as too far away to make a difference.[xviii] The City Hurricane Committee professed to hear the businessmen’s concerns, urging that yet another urban barrier farther south at Fields Point should be built “with the least possible delay”–but that was 1955, and the idea had long since receded from public memory (though it has recently resurfaced).[xix]

The USACE refined their plans for hurricane surge prevention over a span of several years.[xx] To simulate future storm scenarios, ACE engineers built a giant model of Narragansett Bay and Rhode Island Sound in an airport hangar in Vicksburg, Mississippi. In all, it was about a third of an acre in size, modeling the area between Point Judith and Westport Harbor going east to west, and from Block Island to the Blackstone River in Woonsocket going south to north, including all the tributary waterways of Narragansett Bay.[xxi] Raised walkways enabled engineers to make observations as if from thousands of feet in the air, while a first-of-its-kind “hurricane surge machine” simulated the impacts of a 20.5 foot surge on the model bay environs below. [xxii] The results of those simulations would decide the shape of the real hurricane barrier that state and city leaders eagerly awaited.

ACE completed construction of the Fox Point Hurricane Barrier in January 1966 at a cost of $16.2 million (roughly $1.5 billion in 2023 dollars.)[xxiii] Then as now the highest hurricane barrier in the country, it was designed to protect 1.1km of downtown land, most of it fill, where tidal surges have historically exacted the worst damage.[xxiv]

The most visible feature of the Barrier is its three river gates, ordinarily suspended like giant storefront awnings above the river’s mouth. Earthen dikes offer added protection on either shore, with five vehicular passages cut through them for the ordinary circulation of traffic. A system of five pumps evacuates water from the inland side when the barrier is closed, while beneath ground, sewer gates stand ready to prevent storm-related backflow.The whole apparatus is powered by high-voltage electrical lines, one of which is linked to a generator in case of grid failure. [xxv]

As luck would have it, the city has not seen another storm surge like those of 1938 and 1954 since the FPHB was installed. However, the barrier has spared the downtown district from nuisance flooding from smaller storms, including Hurricane Gloria in 1985 and Hurricane Bob in 1991.[xxvi] In 2010, after years of deferred maintenance, the USACE assumed control from the City of the main gates, canal gates, and the pumping system. They have since completed $20 million in upgrades in partnership with the city, and the FPHB is now regularly subject to test runs.[xxvii]

Infrastructures connect, and it is this connective capacity that is often foregrounded in ethnographic as well as historiographic studies of infrastructure. Brian Larkin, for example, defines infrastructures as “built networks that facilitate the flow of goods, people, or ideas and allow for their exchange over space.”[xxviii] But as a parallel literature emphasizes, infrastructures just as often disconnect. “Every connection has an equal disconnection orthogonal to it,” as Reviel Netz observes, even if the connection is generally “easier to perceive” than what is riven or foreclosed.[xxix] In fact, for certain kinds of infrastructure, disconnection is the primary intended function, even if the act of keeping apart intensifies the flow of something—for example, capital–on either side of the line that divides what was once contiguous.

The Fox Point Hurricane Barrier is one such purposively dis-connective infrastructure. It was designed to keep Narragansett Bay at bay, and thus to keep Providence, or at least a part of Providence, permanently dry.

In this way, the FPHB was not so much something new at the time of its installation as it was the culmination, in a high-modernist mold, of the hydrocolonial project of “reclaiming” land from water that had long driven the city’s capital growth.[xxx] As one report concluded, the FPHB, along with waterfront highways, completed “a more than century long process of making the rivers, the very reason for Providence’s location, inaccessible, out of sight and out of mind.”[xxxi]

The FPHB thus fixed a potentially fatal breach in the spatial enclosure that was “downtown,” where local urban capital and government had centered, so that tidal waters could no longer threaten to sink it. The downtown was thus re-established as a place outside of the time of the estuary that had given shape to the landscape since the last glacial age. And in this way, the completion of the FPHB was a very significant step in the decoupling of the city at large from its hydro-ecological substrate.

And yet, ironically, the longer-term effect of the FPHB was rather contrary to the logic of the process that it technically advanced. By promising to turn the rivers from volatile agents to fixed and stable features, the FPHB also set the stage for the rivers’ literal re-discovery at century’s end. In other words, without a giant dam to keep it dry, the waterfront would almost certainly not have become the locus of new downtown development, including residential development, that it has been for the last forty years.

As others have observed, what infrastructure does, and how, is subject to change over time.[xxxii] The role of specific infrastructures in socio-ecological imaginaries shifts, as do their socio-ecological effects and relative functions within larger assemblages.

The FPHB is one of those infrastructures that has become something other than when it was first installed. At the time of its construction, the FPHB was conceived as a sort of insurance policy, written in cement, against the threat of hurricane flooding, which had bedeviled the city’s downtown for centuries. By apparently solving the district’s oldest and biggest problem, it allowed city officials and financial stakeholders to resume forgetting that downtown was built in the floodplain of a tidal river (even as the rest of the urban coast remained vulnerable).

The river did not go away, of course. Rather, in ways that mid-century planners had not foreseen, the FPHB ironically enabled that part of the river on the inland side of the FPHB to become something else, at least for a time: a benign presence that could be safely re-discovered and re-remembered as the key to the district’s lost vitality.

To date, the Barrier has been successful, which is to say that Ronnie Davey’s vision hasn’t yet come to pass. But insofar as the FPHB was meant to save downtown from “going under” economically, it failed, and in fact the early seventies marked the beginning of a long nadir. All the downtown department stores were closing in those years. Its office buildings were also emptying out. The Outlet store, where Davey stood to her knees in water, shut its doors in the early 1980s. The shell of it burned to the ground in 1986.

The Barrier could not keep district commerce afloat, because water was ever only one of several factors in downtown’s decline. Nonetheless, from behind the scenes, as it were, the FPHB did achieve a certain pacification of water that downtown planners and stakeholders had long sought. This, in turn, enabled a later cohort to “rediscover” the downtown “waterfront” as a benign and even value-adding feature of the post-industrial landscape–at least for a time. And so, the Barrier and the spatial realignments that followed from it were new-not-new—a means “to change things radically to make sure that nothing really has to change.”[xxxiii] And what’s changed least of all is the normative socio-ecological disconnection of land from water, which is to say the closing off of downtown, a former estuary, from the unruly worlding of tidal flows.

Much of the downtown river system was paved over in the last century for roads and parking lots, and the inner banks of the Providence River were lined with highway ramps—but only hints of these former uses remain. Today, walkways and small parks provide continuous public access, and the rivers are once again a defining feature of the downtown environment; a “central, orienting downtown spatial element” that has catalyzed the district’s continued postindustrial revival.[xxxiv]

But are these downtown rivers actually rivers? I have heard people who are newer to the area refer to them as canals, which makes sense. They are relatively narrow, mostly straight, walled, and disconnected from their floodplain. Most importantly, like other canals, they are constitutively artificial, representing what prior urban regimes determined to be water’s minimum necessary presence for purposes of navigation and drainage.

Well before the rivers had become canals, under the care of Narragansett people, the whole downtown district and beyond was a radically different place: an intertidal zone where two contiguous water bodies—the Great Salt River and the Great Salt Cove—supported a great diversity of life.[xxxv] It was also a place where many paths intersected, and “where Indians of different tribal affiliations lived, worked, and socialized.”[xxxvi] “Downtown,” possibly more than ever since, was thus a social and ecological crossroads, sustained by water (see Figure 7).[xxxvii]

And though reclamation has been a fait accompli since the 1890s, land and water are still kept strictly separate–even over recent years, as planning and development have reoriented to the rivers in the form of public parks and new construction. I take care to “recollect” this process, not because it is exceptional—cities were built and later reinvented in similar ways across the Northeastern U.S.–but because it is too-little-acknowledged, and when acknowledged, too-narrowly framed, such that the cultural and ecological richness of what was destroyed is barely registered.

[i] An Anglicized rendering of the indigenous word Nahahiganseck, Narragansett means “the people of the small points” (i.e., the Bay’s fingered coastline). Lorèn Spears, Executive Director of the Tomaquag Museum, “Indigenous People in the Narrow (Pettaquamscutt) River Watershed” (Narrow (Pettaquamscutt) River Watershed, July 12, 2019), accessed April 24, 2024, https://narrowriver.org/indigenous-people/.

[ii] McCabe, Carol, “Nothing Says Lovin’ like Meeting with the Coven,” Providence Sunday Journal (RI), March 11, 1973, E1.

[iii] https://www.hurricanescience.org/history/storms/1950s/carol/; https://www.etymonline.com/word/monster

[iv] Providence Emergency Management Agency, City of Providence Local Hazard Mitigation Committee, and Horsley Witten Group, Inc., “Strategy for Reducing Risks from Natural, Human-Caused and Technologic Hazards: A Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan” (City of Providence, April 2019), 27.

[v] “Hurricanes: Science and Society: 1954- Hurricane Carol,” accessed July 14, 2021, http://www.hurricanescience.org/history/storms/1950s/carol/.https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/outreach/history/#carol

[vi] Providence Emergency Management Agency et. al., “A Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan,” 27.

[vii] Cady, The Civic and Architectural Development of Providence, 81.

[viii] Providence City Plan Commission, Downtown Providence, 1970, xii-xiii.

[ix] “Hurricane Dam Bond Issue on All Ballots,” Providence Journal (Providence, Rhode Island), October 30, 1960: N-28; “Inflation Calculator,” accessed December 10, 2023, https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1954?amount=50000000.

[x] Providence Journal (Providence, Rhode Island), October 30, 1960: N-28.

[xi] “Senate Group Hears RI Case for Hurricane Study Priority,” Providence Journal (Providence, Rhode Island), April 21, 1955: 1, 15: 15.

[xii] D.J. Rasmussen, Robert E. Kopp, and Michael Oppenheimer, “Coastal Defense Megaprojects in an Era of Sea-Level Rise: Politically Feasible Strategies or Army Corps Fantasies?,” Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management; American Society of Civil Engineers 149, no. 2 (February 2023), 1–14: 6.

[xiii] City Plan Commission, Downtown Providence, 1970, 57.

[xiv] “Senate Group Hears RI Case for Hurricane Study Priority,” Providence Journal (Providence, Rhode Island), April 21, 1955: 1, 15, 15; Rasmussen et. al., “Coastal Defense Megaprojects,” 5.

[xv] Rasmussen et. al., “Coastal Defense Megaprojects,” 6.

[xvi] Ibid., 7.

[xvii] “Public Endorses Flood Barriers,” Providence Journal (Providence, Rhode Island), October 2, 1956: 1, 20: 20; Also see Rasmussen et al, “Coastal Defense,” 6-7.

[xviii] “Public Endorses Flood Barriers,” 20.

[xix] “City Hurricane Committee Urges Fox Point Dam Now,” Providence Journal (Providence, Rhode Island), May 25, 1955, 1, 27. A new proposal for a hurricane barrier at Fields Point (modeled on a barrier in the Dutch city of Rotterdam) was introduced in 2017 by a research team led by Austin Becker, Associate Professor and Chair of Marine Affairs at the University of Rhode Island. See Austin Becker et al., “Stakeholder Vulnerability and Resilience Strategy Assessment of Maritime Infrastructure: Pilot Project for Providence, RI” (University of Rhode Island – Department of Marine Affairs, May 1, 2017), https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.18743.27040.

[xx] Rasmussen et al, “Coastal Defense Megaprojects,” 9.

[xxi] “In Miniature: Surging Tidal Floods Sweep Narragansett Bay,” Providence Journal (Providence, Rhode Island), May 27, 1956: 1, 27: 27.

[xxii] “In Miniature,” 27.

[xxiii] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “CPI Inflation Calculator,” accessed December 10, 2023, https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.

[xxiv] Rasmussen et al, “Coastal Defense Megaprojects,” 3.

[xxv] Providence Resilience Partnership et al., “Towards a Resilient Providence: Issues, Impacts, Initiatives, Information,” February 2021., 63.

[xxvi] Alex Kuffner, “Rising Threat: Can Providence’s hurricane barrier withstand accelerating pace of sea-level rise?”, Providence Journal (RI), March 31, 2019:,A1; Joukowsky Instutute at Brown University. “Remembering Providence’s Hurricanes.” ARCH 1710 Architecture and Memory (Spring 2009), accessed September 14, 2022, https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/courses/architectureandmemory/8084.html.

[xxvii] Kuffner, “Rising Threat,” A1.

[xxviii] Brian Larkin, “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” Annual Review of Anthropology 42 (2013), 327–43: 328.

[xxix] Reviel Netz, Barbed Wire: An Ecology of Modernity (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2004), 235.

[xxx] James C. Scott defines high modernism as “a strong…version of the beliefs in scientific and technical progress that were associated with industrialization in Western Europe and North America from roughly 1830 until World War I. At its center…supreme self-confidence about continued linear progress, the development of scientific and technical knowledge, the expansion of production, the rational design of social order, the growing satisfaction of human needs, and, not least, an increasing control over nature (including human nature) commensurate with scientific understanding of natural laws” James C. Scott, Seeing like a State How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed / (New Haven : Yale University Press, 1998.), 89-90.

[xxxi] Jay Farbstein and Bruner Foundation, “Creative Community Building: 2003 Rudy Bruner Award for Urban Excellence” (Cambridge, MA: Bruner Foundation, 2004), 93.

[xxxii] Nikhil Anand, Akhil Gupta, and Hannah Appel, eds., The Promise of Infrastructure, School for Advanced Research Advanced Seminar (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 17-18; Susan Leigh Star and Karen Ruhleder, “Steps Toward an Ecology of Infrastructure: Design and Access for Large Information Spaces,” Information Systems Research 7, no. 1 (1996), 111–34; Stephen Graham, Disrupted Cities: When Infrastructure Fails (New York: Routledge, 2010).

[xxxiii] Henrik Ernstson and Erik Swyngedouw, “Politicizing the Environment in the Urban Century.” In Henrik Ernstson and Erik Swyngedouw, eds., Urban Political Ecology in the Anthropo-Obscene: Interruptions and Possibilities, 1st ed., vol. 1, Questioning Cities (Milton: Routledge, 2019), 1-32: 7.

[xxxiv] Brent D. Ryan, “Incomplete and Incremental Plan Implementation in Downtown Providence, Rhode Island, 1960-2000,” Journal of Planning History 5, no. 1 (February 1, 2006): 35–64: 49.

[xxxv] Archaeological surveys attest to both the fecundity of the area, and its importance to indigenous communities. See Ora Elquist et al., “Providence Cove Lands Archaeological District (RI 395) Supplemental Report” (Pawtucekt, RI: The Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc, November 2019). On the non-universality of seeing, and fabricating, rivers as discrete entities, see Dilip da Cunha, The Invention of Rivers: Alexander’s Eye and Ganga’s Descent, Penn Studies in Landscape Architecture. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019); also Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha, “Wetness Is Everywhere: Why Do We See Water Somewhere?,” Journal of Architectural Education (1984) 74, no. 1 (2020): 139–40.

[xxxvi] Patricia E. Rubertone, Native Providence: Memory, Community, and Survivance in the Northeast (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020).

[xxxvii] Christine M. Delucia, Memory Lands: King Philip’s War and the Place of Violence in the Northeast, The Henry Roe Cloud Series on American Indians and Modernity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 126. In Providence, indigenous people were not initially displaced by English settlers. Rather, as Lorén Spears, Executive Director of the Tomaquag Museum, explained to me, the English town of Providence was akin to a vassal state vis-a-vis the Narragansetts’ jurisdiction over the West Bay area of what became Rhode Island. Christine DeLucia writes that in letting the English stay, “Native leadership strategically decided to bring (Roger) Williams into Native space and into a preexisting set of relations, rights, and responsibilities.” Native people thus continued to travel freely through Providence by way of the ancient roads that bisected it, with the English houses along “Town Street” (present-day North Main Street) being just one stop along the route. Providence founder Roger Williams accordingly described the settlement as a “thoroughfare town” where, as Patricia Rubertone writes, “colonists, including Williams, entertained Indians who dwelled in and passed through” the area. This relatively peaceable arrangement lasted for about forty years. Sources: Lorèn Spears, Executive Director of the Tomaquag Museum, interview by Samia Cohen, September 28, 2022; Delucia, Memory Lands, 126; Patricia E. Rubertone, Native Providence: Memory, Community, and Survivance in the Northeast (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020), 7.